Chronicles of Klept: Chapter II

The screams came first—cutting through the air like a sharp gust of wind, out of place amid the laughter and music of the festival. Fires broke out on the treeline, their crackling smoke staining the air, and chaos descended upon the festival in an instant. Swords clashed. People ran. Guards tried to form a perimeter, but it was too late.

As the attack unfolded, I found myself, for the first time in my life, paralyzed by indecision.

I hid—yes, I am ashamed to admit it. I found refuge behind a stack of kegs near the stage, hoping to remain unnoticed, to not draw attention to myself. I felt like a coward.

The attackers weren’t showy—not at first. Dark cloaks. Hoods up. Faces hidden. The kind of anonymity you don’t question during a crowded celebration. They moved with quiet purpose, carrying simple but brutal weapons—nothing flashy, just the sort of things that make quick, efficient work of unarmed men trying to balance a slice of pie and a mug of pumpkin-spice brandy.

They struck fast.

Some of the guards didn’t even get their weapons drawn. One, I’m fairly certain, was still chewing when he went down. The rest tried—gods know they did—but you can’t blame them for being unprepared. The only conflict they’d been expecting that day was between pie vendors.

Whoever these cloaked figures were, they had a plan. And that plan, I now realise, centered on the High Reader. Possibly on me as well. And the other Readers present.

I suspect they hadn’t accounted for one very specific variable: the kind of chaotic heroism that only absolute strangers can achieve when they have no idea what else to do.

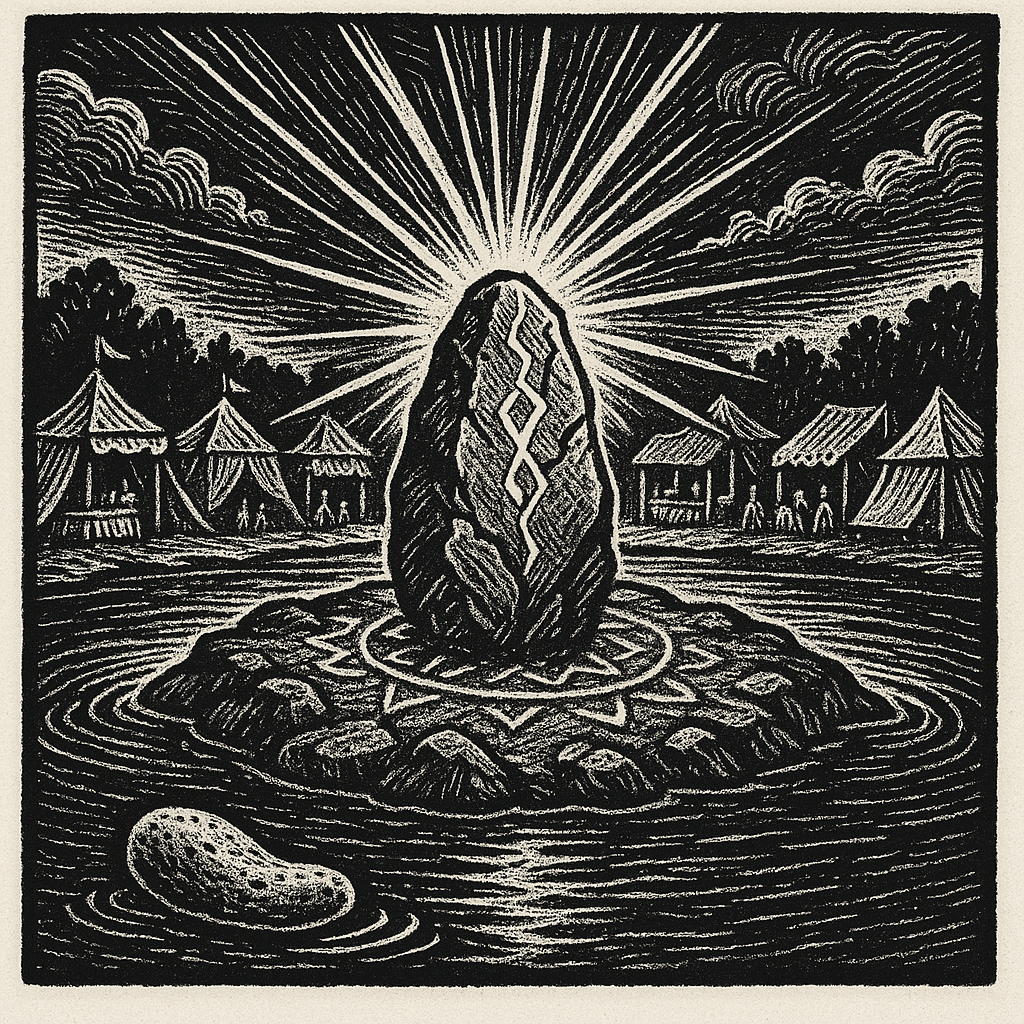

I watched as a group of outsiders, who had seemed little more than curious bystanders earlier, suddenly converged on the stage. Among them, the gnome, still stranded on the Prophet Rock, and the tall, long-haired elf who had earlier discarded his oversized bean into the water.

The gnome was at a disadvantage—marooned on the rock, with no means of crossing the water. But instead of waiting for aid, he turned to magic, sending flashes of arcane energy hurtling toward the attackers across the lake.

Then, in the span of a breath, he was gone.

Not by foot. Not by boat.

He simply vanished.

And then, impossibly, reappeared on the shore, near the stage, and continued to hurl beams of energy at these mysterious attackers.

From the moment the blades were drawn, the group that would come to redefine the phrase “helpful disaster” leapt into action.

At times, they moved like a unit—fluid, decisive, unstoppable. Other times, it was like watching several different theatre troupes perform several different plays on the same stage at once.

A particularly furious gnome charged headlong into the chaos with an axe nearly as tall as he was. He missed his target, but nearly took off the leg off the festival stage in the process. He punched himself in the chest and took a second swing, this time his true target crumpled in front of him.

The long-haired elf, all calm precision and razor-sharp swordplay, danced through the fray like he was trying to choreograph the world’s deadliest waltz.

A wild-looking halfling, wielding what appeared to be a homemade bow, dropped several attackers with terrifying accuracy. No flourish. Just results.

And somewhere in the chaos, I could have sworn I saw one of the cloaked attackers turn on his own. A flash of movement, a blade redirected. Intentional or not—I couldn’t say.

What I can say is this: no one knew who they were when they stepped in. But everyone knew something had shifted by the time the dust settled.

When the last of the attackers fell, the festival quieted—not with victory, but with a heavy silence.

Those who had survived the battle began to tend to the wounded. Guards rushed to put out the flames, and the priests—including Tufulla—began to offer prayers for the fallen.

I remained behind the barrels. I stayed hidden for some time, too ashamed to step forward, too uncertain of my place among those who had taken action.

I had watched. I had done nothing.

But in the silence of the aftermath, as the chaos subsided, I realized who had taken charge. It was not the guards, not the priests, but a group of strangers—a gnome, an elven traveler, and a handful of others I had never seen before.

They had stepped into the breach.

And I did not know why.