Chronicles of Klept: Chapter XXIV

It wasn’t long before the squeak of wheels and the soft clop of mule hooves on packed dirt were joined by the gentle sound of snoring.

Trunch had wedged himself between two packs near the back of the cart, a faded raincloak bundled beneath his head like a makeshift pillow. The cart jolted and creaked beneath him, but he was already fast asleep — mouth slightly open, hands folded across his chest, a look of childlike innocence softening his features. The rise and fall of his chest was occasionally interrupted by a flicker of dark energy crackling across his fingertips.

He looked peaceful.

Except for the shadows.

They didn’t quite match the rhythm of the cart’s movement — just a fraction too slow to follow, a fraction too eager to reach.

Yak sat near one edge of the cart with the ease of someone who had done this a thousand times – and with the glee of someone who was delighted each time as if it were the first. Legs swinging freely, a leather pouch bouncing at his hip, a smudged notebook balanced on one knee. Every so often, he’d leap down without warning and dart into the brush or to the roadside where a tree or flowering shrub caught his eye.

He sniffed, pinched, and occasionally nibbled at leaves, petals and bark, scribbling quick notes in cramped, inky handwriting. Then, just as suddenly, he’d strike, a flick of a small blade slicing a bloom or strip of bark free with surgical precision. More than once, he was back on the cart before the plant had finished swaying from the force of his cut.

There was something undeniably innocent about the way he perched there between bursts of activity; legs swinging, humming to himself, pleased by whatever strange alchemy he was planning. But the speed with which he moved gave his actions an edge. It was hard to say whether he was picking ingredients or hunting them.

He returned each time with eyes dancing. Sometimes he held up a leaf for the others to admire, only to tuck it away without waiting for a response. The cart ride settled into a strange rhythm: leap, nibble, sniff, slash, scribble.

And though he always smiled, it was hard to say what that smile looked like. Around strangers, Yak’s face became something slippery and forgettable. Constantly changing and unknowable. But even here, among friends, his features were oddly blank, almost like a placeholder for a person. You could stare at him for minutes and still not recall the color of his eyes. Only the smile remained. Unsettlingly constant. Unfailingly cheerful.

Wikis spent most of the journey watching the sky as though she believed it wasn’t being truthful.

She perched near the front of the cart, hood pulled low, eyes narrowed, scanning every passing cloud with the intensity of someone waiting for a very specific kind of doom to arrive. Her fingers toyed constantly with the drawstring of the small pouch at her hip, the one that jingled faintly with the weight of coins, buttons, fragments of mirror, and other shiny trinkets no one else had dared ask about.

She muttered to it often.

Every few minutes, she’d open it with great suspicion, rifle through its contents, and breathe a sigh of relief. Then she’d glance sharply at whoever was closest, brows drawn tight with narrowed accusation.

Once, she scurried forward along the cart’s wooden lip, across the reins with surprising balance, and leaned in close to one of the mules. She whispered something low and urgent into its ear. Then, just as quickly, she darted back, climbing over Day’s shoulder like a raccoon and tucking herself behind a pile of packs with a nod of satisfaction.

She tried hiding behind Carrie for a while although it was less hiding and more crouching very visibly in the open and insisting she was unseen. Every so often, she peeked out to glare up at a patch of sky that seemed slightly too empty for her liking, or slightly too full.

Her bow lay across her knees the entire time, fingertips brushing it occasionally, not as a threat, but more like a reminder. No one had taken anything from her pouch. But that didn’t mean they wouldn’t.

She seemed to think the sky definitely knew something.

Umberto sat cross-legged, reading a well-worn copy of Barbara Dongswallower’s A Tight Fit, his thumb tracing along the spine like it was something sacred. The cart jostled and groaned beneath him, but he didn’t seem to notice. He was deep in the pages, lips moving silently as he read.

He let out a satisfied grunt.

“There it is,” he whispered, nodding to himself. “The perfect example. Right there.”

He winced and rubbed his jaw, then touched the side of his face with two fingers, gently testing the tenderness of the bruise.

“Totally worth it,” he muttered. “How anyone could possibly think Barbara Dongswallower’s prose is anything but the height of literary perfection is beyond me.”

He shook his head and scoffed mockingly, “Oh, her prose is awful. She obviously uses a ghost-writer.”

Then, louder — to no one in particular, but loud enough for everyone to hear — he read:

“Their gazes collided like charging stallions on a moonlit moor, breathless and wild. His voice was gravel soaked in honey, scraping sweetly against the hollow of her hesitation. And when his fingers grazed her greaves, she didn’t just tremble — she unraveled, one thread at a time, until she was nothing but longing laced in plate.”

Somehow, he rolled his eyes in both derision and ecstasy.

“I mean, come on. Nuance. Subtlety. Structure. That guy and his idiot friends deserved the lesson in literary appreciation.”

He rubbed the side of his face again and resumed reading with a sense of righteous conviction, the bruising along his cheek catching the sun as he smiled softly to himself.

Day looked at me and shrugged.

Carrie fluttered nonstop. From the moment the cart left the Dawnsheart, to the moment the Prophet Rock loomed into view, she buzzed from person to person like a winged monologue generator, trailing sparkles and unrelenting commentary in her wake. She didn’t wait for responses. Didn’t need them. It was less a conversation and more a performance. Delivered in acts, punctuated by costume changes, and underscored by the faint shimmer of fairy dust clinging to her wake.

“That cloud looks like a muffin,” she told Umberto, who didn’t look up from his novel. “A sad muffin. I bet it has emotional baggage.”

Later: “Do you think mules ever dream of being ponies? Or like, war horses? Or peacocks?”

At one point she pulled out her bagpipes and launched into a triumphant, if uneven, rendition of The Ballad of the Soggy Goat. Yak applauded with genuine delight, throwing flower petals at her like a drunken wedding guest. Carrie bowed midair, blew a kiss, and stuffed the flowers into her corset with a dramatic gasp of gratitude, as though she’d just won a lifetime achievement award.

Eventually, her attention turned to the mules.

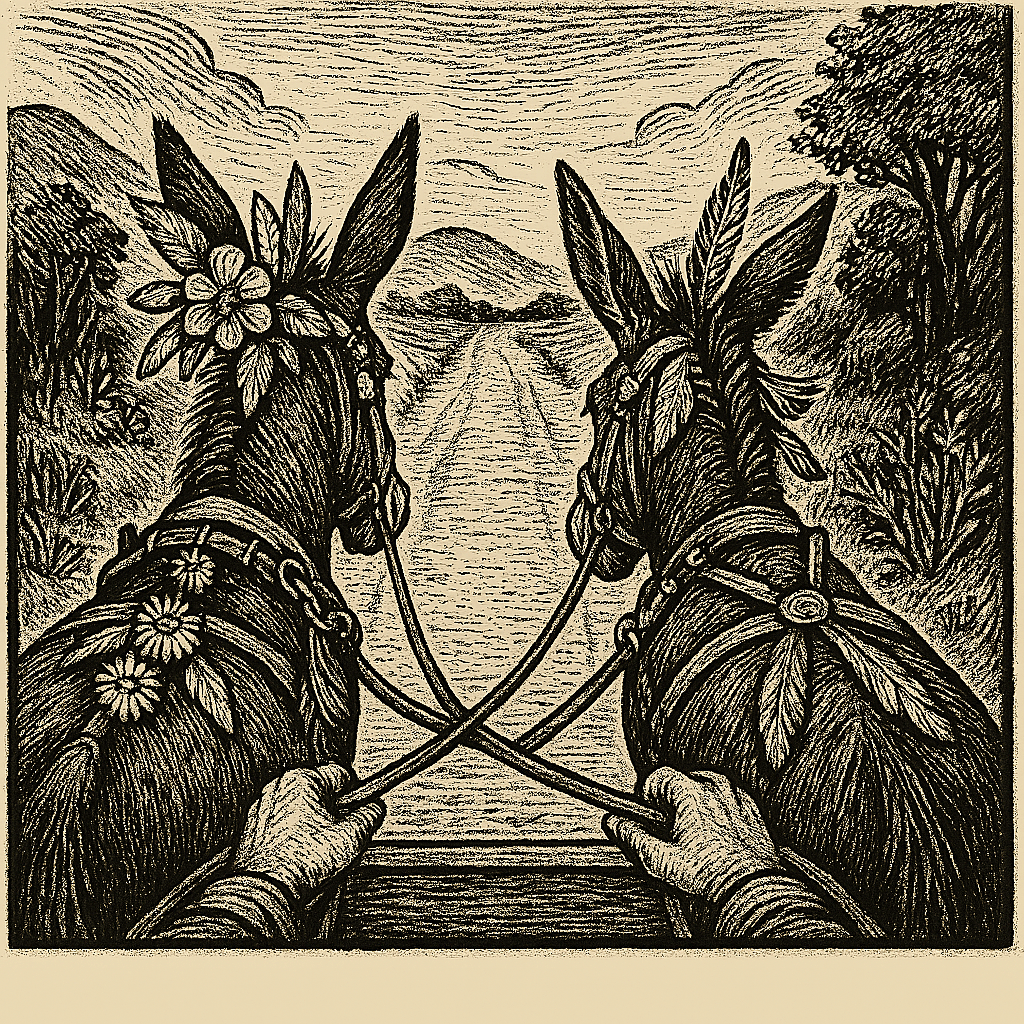

This began innocently enough: a little petting, a little cooing, a few whispered compliments. Then came the glitter. Then feathers. Then braided manes, makeup, a decorative sash made from a strip of old curtain she swore wasn’t stolen, and what might have once been one of Trunch’s handkerchiefs now acting as a headband across one mule’s brow.

By the time she was finished, the mules looked like parade float rejects—proud, sparkling, faintly horrified.

“Stunning,” Carrie declared, fluttering between them, hands on hips, admiring her work. “Absolutely radiant. If we run into any bandits, they’ll be far too intimidated by the sheer confidence of these looks to attack us.”

When not fluttering between the cart’s occupants and her newly beautified beasts, she twirled slowly above the wagon, arms outstretched, catching falling leaves and assigning each of them names and scandalous backstories. Somewhere around the midpoint of the journey, she adopted a small stick, named it Madame Dewsnap, and insisted it was the group’s moral compass.

While Carrie directed the mules through their glitter debut, Din and Day pressed me for details. Before we’d left, Tufulla had handed me a stack of parchment—updates, intelligence, scattered notes—meant to help us piece things together and prepare for whatever storm was brewing.

“There’s a note here,” I said, flipping through the stack and holding one out to Day. “Something about another stump being found. In the forest outside Briarbright.”

Day frowned, studying the parchment. “No doubt they’ll find more soon. Briarbright?”

“The Briars,” I replied. “It’s the half of the city across the river,” I clarified.

Din leaned over, plucking the page from Day’s hands. “Trunch mentioned that once, didn’t he? Something about one city becoming two?”

I nodded. “The Briars used to be one city, Briarton: larger than Dawnsheart, actually. It straddled the Crystal River. But centuries ago, a family dispute broke out, an argument over which heir should lead. They never settled it. So the city split, clean down the river.”

“They just… split the city in half?” Day asked, eyebrows raised.

“Right down the middle. It’s been two separate towns ever since – Brightbriar and Briarbright. And no, they never reconciled. No one even remembers what the original argument was about, but the grudge stuck. There’s only one bridge between them now, and it’s heavily guarded on both ends, just in case anyone gets nostalgic and tries diplomacy.”

I flipped through the parchment until one sheet caught my eye. I passed it to Din. “You might find this interesting.”

My eyes skimmed the text—years of scribing had made quick reading second nature. “There was an attempt on the King’s life. The Royal Guard’s been disbanded.”

Day leaned in, peering over the page. “Really? During the harvest festival? That’s bold.”

“Looks like one of the bodyguards was killed. Another was arrested—accused of being part of the plot. The Brothers of Midnight ran an internal investigation and uncovered several others in the Guard who were complicit.” Din’s brow furrowed as he read.

“That’s… serious. Treason inside the palace guard?” Day questioned.

“Seems so. The entire Guard was dissolved. The Brothers of Midnight took over.” Din handed the parchment back to me..

“Brothers of Midnight?” Day glanced at me.

“Elite splinter group,” I said. “Formed from the Royal Guard. Their job is to protect the royal family during the dead of night—silent operatives, moving in shadows. The kingdom’s hidden hand. Loyal, lethal, and invisible when they need to be.”

“Rumor has it they operate on two fronts” Yak’s voice cut in over Carrie’s bagpipes. “There’s a division that stays in the capital and another that operates around the continent.”

Day gave a low whistle. “Well. They sound like a group you don’t want to piss off.”

I flipped further through the stack. “Ah. Here we go. The White Ravens have confirmed increased undead activity. Scattered groups throughout the valley, most of them… drifting.”

“Drifting?” Din asked, leaning over again.

“Apparently not attacking. Just walking. All headed in the same direction. Toward the mountains.”

Day frowned. “Like Wikis and Umberto, back at the stump.”

I nodded. “Castle Ieyoch. That’s the implication. They’ve counted at least four dozen distinct shamblers. Some groups as small as two or three. A few large enough to be dangerous.”

“Only within the valley?” Din asked.

“I’m not sure,” I said, flipping to the next page. “A few sparse sightings outside. All heading the same way – toward the Humbledoewn Valley.”

“Drawn to something,” Day murmured. “Or someone.”

There was a silence as we let that settle.

I reached for another sheet, thinner than the rest, its ink faded but precise. “Huh.”

“What is it?” Din asked.

“It’s a historical note,” I said, “about a celestial event—an eclipse, centuries ago. Lasted several days.”

Din raised an eyebrow. “That doesn’t sound normal.”

“It isn’t. Wasn’t,” I replied. “At least, not naturally. According to this, the eclipse coincided with the rise of the Dan’del’ion Court. Some believed it was a bad omen. Others thought it was unnatural, intentional.” Day pursed his lips and nodded. “One scholar posits it wasn’t an eclipse at all, but a ritual cloaking of the sun. Apparently it started with the removal of the stars from the night sky. Whatever that means.”

“Lovely,” Day muttered, exhaling sharply. “A kingdom of shadows rising in darkness. Of course they’d start with the sky.”

Din steepled his fingers, “If we can believe anything Dominic said, before he revealed himself – he said there was an army at the castle waiting for an event.”

“You think they’re waiting for another eclipse?” Day asked.

“You said they were vampires, some of them.” Din looked at me. “It makes sense. That would be a good time for them to attack. No sun.”

“Possibly. Or maybe it’s a ritual.” I folded the parchment and slid it back into the stack. “Either way, we’ve got little information and less time.” My gaze drifted up the length of the cart.

Wikis sat perched with her hood drawn tight, still glaring up at the sky. Her hand hovered near the pouch at her hip. The other over the bow on her lap. A cloud passed overhead, and her eyes followed it like a hawk.

I turned back to the parchment.

“Do you think she senses something?” I asked, quietly.

Din shrugged, “She’s been watching the sky all morning. Maybe she knows what’s coming.”

“Maybe,” Day replied. “Or maybe she’s mad.”

“Not always mutually exclusive,” I said.

A gust of wind stirred the trees.

Wikis narrowed her eyes at the clouds again, like she was waiting for them to blink.

The Kashten Dell was quiet. On its edges, sun-dappled trees swayed gently in the afternoon breeze, their leaves rustling in soft conversation. Birds chirped lazily from the branches above, and the hum of insects buzzed through tall grass and blooming wildflowers, blues and yellows and white-starred purple, growing in cheerful defiance of the beaten path.

It wasn’t bustling. Outside of the Harvest Festival and the Reading, it never was. Just a few scattered travellers, the occasional creak of a wooden cart in the distance, and the still, reflective surface of Prophet Rock lake.

The last time we’d seen the Dell, it was chaos — tents on fire, people screaming, smoke curling through the trees, the ground slick with blood. Now… It was peaceful. Calm. Serene. As if the land itself was trying to forget.

Now, we’d come in search of Hothar, a firbolg druid who protected the surrounding wilderness and was once a part of an adventuring team that had scouted Castle Ieyoch, but no one in the Dell seemed keen to talk about him. Or maybe they didn’t know him at all. We weren’t sure which. An old woman seated on a rock beside the road just laughed and waved us away. Umberto didn’t take it well.

“Big guy,” Din said to a man fishing at the edge of Prophet Rock Lake. “Tall. Looks after the place. Might wear moss.”

The fisherman shrugged and pointed vaguely toward the woods, “Haven’t seen him in a few days. His hut is just over there, beyond the tree line.”

We headed in the direction the man had indicated and found a small, makeshift shelter; a simple roof woven from twigs and leaves, balanced atop four thick branches driven into the ground. A sleeping mat lay off to one side. Nearby, a pot and a blackened kettle hung over a small firepit, the ashes cold and gray – untouched for several hours, at least. Dried herbs hung in neat bunches from the ceiling. Clay bowls filled with berries and nuts sat carefully arranged on a flat stone.

It didn’t look abandoned.

But it didn’t look lived in either.

We called out a few times, but there was no answer. The woods stayed quiet.

Yak wandered over to one of the clay bowls, picked out a berry, sniffed it, then gave it a tentative lick.

Din didn’t even look up. “Put it back.”

Yak sighed and dropped the berry back into the bowl with exaggerated disappointment, wiping his tongue on his sleeve.

Trunch wandered down toward the lake and stopped at the edge of the water. He stood there for a while, just… looking. Then he tossed a small stone and watched the ripples drift outward where it fell.

“You gonna climb it again,” Umberto asked, eyeing the Prophet Rock with renewed interest.

Trunch shook his head. “No,” he said quietly. “Not this time.”

Umberto turned. “Why not?”

Trunch didn’t answer right away. He just stared at the rock.

“I don’t think it would be respectful,” he finally said. “And… part of me wonders if what I did started something we didn’t understand.”

Umberto nodded and shrugged.

Trunch tilted his head. “Also … I can’t actually swim.”

We waited. We searched. We asked a few more questions to the handful of people still lingering nearby, but no one could point us toward him.

“Hothar?” A portly man with a sun-reddened nose paused mid-step, his wiry mule snorting behind him beneath a tower of bundled fabrics. “Big fella, gentle as rain? He’s always pokin’ around the woods — talking to trees, rescuing birds, that sort of thing. Sort of nature’s warden, y’know? Usually shows up when something needs fixing. Or when the squirrels start organizing again.”

He scratched his head beneath a frayed straw hat. “Might be out checking on a grove or a nesting site or who knows what. He comes and goes. Nature business.”

The man chuckled as he adjusted one of the bundles. “If you’re waiting to talk to him… you might be waiting a while. Works on nature’s time, that one.”

After an hour, we gave up.

“We don’t have time for this,” Day said, scanning the treeline. “I think we should move on. Find Travok, he’s next on the list.”

No one argued. We left the Dell behind, the Prophet Rock shrinking behind the trees as we turned north — toward Ravenswell.

“Apparently,” I ran my eyes over the notes Yun and Tufulla had provided about the group, “He runs an inn just outside Ravenswell, the Stumble Inn.”

“Finally,” Umberto snapped. “Somewhere that serves drinks.”

Ravenswell came into view before the Stumble Inn — or at least, the aura of it did.

“I think the forest is on fire,” Carrie gasped as we crested a low hill.

“Chimneys,” I said flatly. “Just chimneys.”

“Chimneys?” Din asked, squinting into the haze. “That many?”

“Welcome to Ravenswell,” I replied. “Industrial hub of the valley. Iron and coal mines in the Marwhera Peaks just behind it. Almost all the valley’s weapons, tools, furniture — they’re made here.”

“Smells like burnt socks,” Yak muttered, wrinkling his nose.

“Doesn’t really fit the rest of the valley,” Day noted.

“It doesn’t,” I agreed. “Everywhere else is farms and forests. Here, it’s soot and sawdust. The best smiths, carpenters, fletchers, coopers — all of them set up shop in Ravenswell. It’s not as polluting as some of the industrial towns beyond the mountains, but in a place like this? The contrast is… noticeable.”

Trunch tapped a finger against his temple. “I read once that the best woodwork on the continent came from this valley. Timberham, wasn’t it?”

I nodded. “Timberham. South of Briarbright. Legendary craftsmanship. The kind of place where chairs were heirlooms and doorframes had waiting lists.”

“And now it’s a ghost town. No one really goes there anymore?” Trunch asked.

“Because of actual ghosts?” Carrie asked hopefully.

“No. Bad memories.”

“What happened?”

“Dan’del’ion Court. They razed it — a warning to the valley. It’s just blackened beams and broken windows now. Very few actual residents.”

Carrie’s eyes lit up. “So, possibly because of ghosts?”

I turned to her. “No. Mostly just abandoned. Possibly cursed.”

She frowned.

I sighed. “Although… given the circumstances and the rumors, I wouldn’t rule out ghosts entirely.”

Several minutes later, just before the edge of Ravenswell proper, the Stumble Inn came into view — a squat, single-storey building of thatch and stone, nestled like an afterthought at the bend in the road. Smoke curled lazily from a small chimney. A modest stable stood to one side, and a C.A.R.T. stand sat nearby, its beast pen empty and its attendant half-asleep.

We led the mules over first. The attendant roused with a grunt — then froze as Carrie’s glittered parade-beasts came into view.

He blinked.

The mule with the braided mane snorted defiantly.

“I can explain,” Carrie chirped, like someone accepting a trophy.

“You really can’t,” Day muttered, patting the mule’s flank.

We left the beasts in his stunned care and made our way toward the inn.

“I’ll stay out front,” Day said as we approached. “Keep an eye out. Just in case.”

Wikis nodded and wordlessly joined him, already half-cloaked in her hood, watching the sky again like it had wronged her personally.

We headed to the door which creaked open with a groan, and stepped into the dim glow of the Stumble Inn.

Or tried to.

Trunch was first — and promptly tripped forward with a startled grunt, catching himself on a table and knocking over a spoon.

The inn erupted in cheers.

Yak and Umberto reached the doorway at the same time. There was an immediate flurry of elbows and shoulders as they jostled for position.

“Move it,” Umberto growled. “I need a drink.”

“Not as much as I do,” Yak hissed back, grinning.

They pushed, twisted, half-tripped over each other — and finally burst through the threshold in a tangled heap.

The room erupted.

Yak landed sprawled and sideways across the earthen floor, arms splayed like a felled starfish. Umberto skidded into a table leg, rolled to his feet, and threw both arms in the air like he’d just won a wrestling match.

Cheers, whistles, and laughter rang out across the inn.

Carrie fluttered in with perfect grace, feet never touching the ground. She landed gracefully on an empty table, twirled and struck a dazzling pose … and was met with complete silence.

She blinked. “Oh come on.”

Din followed next, stepping over the threshold carefully and with intention. A chorus of boos met him before his boots had fully hit the packed earth..

He raised a single brow. “Really?”

“They didn’t stumble!” someone shouted “They buy their own.”

Carrie crossed her arms. “I was being elegant.”

The barkeep shrugged. “Elegance don’t get you an ale.”

She glared at him.

I followed right after them — and stumbled.

My boot hit the raised threshold just a little too high, and the floor dropped just a little too quickly. As I pitched forward, I had just enough time to think, Ah. Slightly elevated entry, lower interior floor. Optical illusion. How clever.

Then I hit the floor, caught myself on a table leg, and was met with thunderous applause.

“Better!” someone yelled.

I straightened, dusted myself off, and gave a short bow. “You people are very enthusiastic about other people falling over,” I observed.

“That’s the whole point.” the barkeep called. “It’s in the name. First timers get an ale on the house, if they stumble in.” He waved a hand derisively, as if he really didn’t care at all.

“Free ale,” Umberto said, downing a mug that was handed to him in a long, satisfying gulp. He exhaled like someone who’d just emerged from underwater. “This place,” he said, eyes closed, “is great.” He turned to Yak, “We need a gimmick.”

It was the happiest we’d seen him all day.

“What brings you to the Stumble Inn?” The individual behind the bar was a squat, broad-shouldered Dwarf. He wiped his hands on a greasy cloth and scowled at us like we’d spilled something.

“We’re looking for someone,” Carrie replied. She leaned in closely, “Someone who is in danger.”

“So, you’re not just passing through,” he said flatly.

“Not just,” Din replied, nodding politely.

The dwarf didn’t answer. Just kept wiping, one eye narrowing.

Umberto set his tankard down. “You wouldn’t happen to know a Travok, would you?”

The wiping stopped.

“Depends who’s asking.”

“We’re friends of Yun,” I offered. “And Tufulla.”

He grunted. “Figures.” He threw the cloth down. “So, you church folk.” He glanced at me.

“We’re not with the Church,” Din said.

“We’re an independent group, ” Carrie cut in “No political affiliations. We’re the Damaged Buttholes.”

The inn keeper raised a brow. “That’s not a real name.”

“Unfortunately, it is,” Din muttered.

Travok looked at me again. “So what’s he doing with you then?” He jabbed a thick finger in my direction.

“I’m just a scribe,” I said quickly. “A note-taker.”

He squinted at me like I was some kind of fungus growing on a loaf of bread.

I cleared my throat. “They – can’t write,” I added, eyeing Umberto pointedly.

Umberto scowled, raised his mug and drank again.

“We’re trying to find out about Castle Ieyoch.” Yak added, “About what happened there.”

The dwarf stared long and hard at Yak. He leaned forward slightly, squinting into the hooded shadows. “You been in here before?” He asked, “You look kind of familiar.”

Yak just smiled. “Me? No, first time patron. I just have one of those faces.”

“The Dan’del’ion Court is rising again.” Trunch added with conviction, “Yun said Travok was part of a scouting team that made it back from the castle. We just want to ask him a few questions.”

Travok’s eyes tightened.

“I don’t talk about that,” he said. “Didn’t then. Don’t now.”

“Why not?” Din asked gently.

“Because I don’t remember.”

The words dropped heavy and bitter.

“So, you’re Travok?” Carrie asked, eyes wide. “I thought you’d be … bigger.”

He scowled.

“That explains the crossbows,” Yak said casually.

Travok’s eyes snapped toward him.

Trunch frowned. “What crossbows?”

“The traps,” Yak said, still not looking at anyone. “Button-triggered, I’d guess. I noticed three separate clicking sounds when we mentioned his name. Above the door, under the bench, and,” he leaned sideways a fraction, “behind that barrel over there.”

Travok stared at him. Then, slowly, he reached below the bar and flipped a small switch with a heavy clunk.

“Built most of them myself,” he said gruffly. “Harmond helped. Old friend.

“Harmond of Beastly Bits. In Dawnsheart?” I asked.

“That’s him. Mad as a goat. Knows his contraptions though.”

“Expecting someone?” Din asked.

“I always expect someone,” Travok snapped. “After I got out of that cursed place, I started having visitors. Mostly at night. Always hooded. Always wearing one of these”

He reached beneath the bar and pulled out a small lockbox. Inside were five identical medallions — the unmistakable emblem of the Dan’del’ion Court.

“Pffft. We’ve got like a dozen or so of those,” Carrie scoffed as she reached into her pack and dumped a cloth wrapped heap on the bar. There was the distinct clink of metal as the cloth parted exposing a pile of medallions. “What’s your point?”

I moved to quickly cover the pile of medallions with the edges of the cloth, “Don’t wave these around in public,” I hissed at Carrie, “They’re highly illegal.”

“No one here gives a shit,” Travok snarled. Then, raising his voice to the room:

“Hey — these…” he glanced at us quickly, “…buttholes have killed a bunch of Dan’del’ion scumbags!”

There was a cheer and the clink of glasses in celebration.

“You’ll find no love for the Dan’del’ion Court here,” he added, with something approaching joy. “May they all die fucking painful deaths.”

Umberto, Yak, and Carrie raised their mugs in silent salute, joined by the majority of scattered patrons throughout the room.

Travok leaned back behind the bar, crossed his arms, and looked us over.

“Right. We’ve done introductions. Now we’re best fucking friends,” he said with a smug curl to his lip, “What in Bragmire’s name do you want?”

There was a beat of quiet. A shuffling of feet. The uncomfortable scrape of barstools. Ale being swallowed a little too loudly.

No one wanted to be the first to speak.

Eventually, Din stepped forward.

“We came to ask you to come with us,” he said. “Back to Dawnsheart.”

Before Travok could respond, the door burst open behind us.

A loud cheer erupted from the patrons as Wikis faceplanted into the dirt just inside the threshold.

A mug of ale was quickly thrust into her hand. She clutched it instinctively, eyes wide, body tense and coiled like a spring.

“Friend of yours?” Travok asked, one eyebrow raised as his hand slipped under the bar.

“She’s with us, yes,” Din answered, calm and steady.

Travok snorted and pulled his hand back. “‘Course she is.”

“Your name is on a list,” Trunch said calmly. “Found on a Dan’del’ion assassin.”

Travok didn’t move.

“There were three of them,” Trunch continued. “Assassins. Working together. The other two are still out there.”

“We took care of one of them,” Carrie added cheerfully, like she was announcing free cake.

Din stepped forward again, locking eyes with Travok.

“The list had names. Members of your team. You. Yun. Hothar. Svaang. And High Reader Tufulla.”

Travok’s jaw clenched.

“Tufulla and Yun both think it’ll be safer if you’re all in one place,” Din finished. “Strength in numbers.”

“They’re killing off anyone who knows anything,” Trunch said. “That’s why we need to get you to Dawnsheart. Tufulla and Yun—”

“I’m not going,” Travok cut him off. “I have this place rigged tighter than the King’s vault. You want me in a safe place? You’re in it.”

“Travok,” Din pleaded, “if we don’t work together, none of us are going to be safe. We’ve already been attacked. People are dying. We need answers.”

“I don’t have answers,” Travok snapped, this time slamming his hand on the bar. “I told you. The Castle was strange. Wrong. We went in… I don’t know what we found. Just pieces. Flashes. Screaming. Fire. A light that wasn’t a light. They took my leg. We made it out. I call that a fair trade.” He stepped back from the bar and tapped his peg-leg against the floor.

“We’re not asking you to fight,” Trunch offered. “Just talk. Help us fill in the gaps.”

“I can’t,” Travok snapped again, this time slamming both hands onto the bar. “That’s what I’m trying to tell you. My memories are… gone. Or missing. There’s gaps I don’t remember. They messed with our heads!”

He looked up slowly and gestured at his tavern.

“Did you stop to wonder why the floor here is just dirt? It’s because I think about that place every time I hear this peg knock against stone or wood,” he said brusquely. “What they did to us. How she didn’t make it out.” Then he drained the last of his ale, stared into the mug like it might refill itself, and muttered, “Go find the others. If they’re still breathing maybe they’ll help.”

“You’re not going to?” Din asked quietly.

“I just did,” Travok said, and turned away. “Now drink up, and get out before I decide you are looking for trouble.”

We started to gather our things. There was an edge to the silence now, like a conversation that had closed too hard.

Carrie lingered by the bar, eyes still on Travok.

“What was her name?” she asked softly. “The one who didn’t make it out.”

Travok didn’t look up. He just exhaled through his nose, like the question had pulled something sharp from deep inside.

“Adina,” he said. “Her name was Adina.”

There was a pause. Then:

“She and Svaang were close. Real close. He can tell you more. If you can find him.”

He didn’t say anything else. Just stared into his empty mug like it held a map to somewhere better.

We stepped out into the mid-afternoon air and found Day casually petting our overly-decorated mules at the C.A.R.T. stand. One of them now had glitter on its ears. The other had feathers stuck to its tail and looked like it wanted to die.

“So,” Day said, not looking up, “I take it he’s not coming with us?”

He said it in that calm, matter-of-fact way that made it sound like he’d known all along.

“No,” Din replied, setting his hammer on the cart with a weary thud. “He’s too stubborn to move and too broken to help.”

Carrie fluttered over and landed lightly on the cart’s edge. “He gave us a name, though,” she said. “Adina. She’s the one who didn’t make it out.”

Day nodded slowly. “I guess that’s something.” He unhooked the mules from the hitching post and tossed the attendant a silver.

Yak stood nibbling a dried biscuit. “He said Svaang would be able to tell us more. Where did Yun say we’d find him?”

“The Briars,” Wikis said, eyeing the nearby treeline. “Somewhere near the bridge.” She climbed onto the cart without breaking eye contact with the trees.

“I say we don’t even bother,” Umberto growled, stomping up to the cart. “Let them get hunted. Fend for themselves. We know where the damn castle is — let’s just go. Kick the door in. End it now.”

Carrie lit up like he’d suggested they crash a royal wedding. “Honestly? That kind of energy is very appealing right now.” She fluttered down beside him, poked his bicep, and grinned. “We storm the gates, you rage, Wikis looses some arrows — boom. Instant legends.”

“I’m in,” Umberto said, flexing his fingers. “We’re wasting time. All this walking and talking — for what? Another name on a list? Another paranoid old fart who won’t help us?”

“No,” Trunch said gently, climbing aboard. “We don’t even know what we’re walking into. Too many variables. Too many unknowns.”

“You’re assuming we have time to figure everything out,” Umberto snapped. “Right now, we’re just dithering around the countryside, talking to ghosts and cowards.”

“And what if we’re walking straight into a trap?” Din said firmly, turning to face him. “The only information we have about the castle came from Dominic — when he was pretending to be Jonath. We don’t know what’s real and what’s bait.”

Umberto scowled, jaw clenched. But he didn’t argue.

Day spoke from the front of the cart, still adjusting the harness on the mules. “We move faster,” he said simply. “Find Svaang. Find Hothar. We go through the Dell on the way to the Briars anyway. We gather what we can.”

He looked back at the group. “The more information we have, the better our odds.”

Umberto exhaled through his nose like a bull barely held at bay. “I swear, if this ends with us back in a tavern discussing feelings—”

“It won’t,” Din said, resting a hand on the haft of his hammer. “You’ll get to hit something soon. Lots of things, probably.”

Umberto snorted, then gave a grudging nod and hoisted himself onto the cart. “You better hope so,” he said, eyeing me as he settled in. “Or I’ll take it out on something else.”

“I promise,” Din said gently, patting him on the shoulder.

I shifted uncomfortably.

Carrie tossed a flower behind her like it was the end of an opera. “Onward, to glory,” she declared. “I feel it in the wind.”

“That’s probably just glitter,” Yak said, brushing some from his collar and climbing aboard.

We urged the mules into motion, hoping they’d pick up the pace now that time actually mattered.

They did not.

If anything, they seemed personally offended by the idea.

The one with glitter on its ears stopped to chew a particularly unappetizing patch of grass. The other let out a deep, sorrowful sigh — the kind that sounded like it had just remembered every bad thing that had ever happened to it.

“This is ridiculous,” Umberto muttered, shifting his weight. “Can’t they move faster?”

Wikis glanced at the mules, then the cart. “Next time we’re in a hurry, maybe we spring for the upgrade and hire horses instead.”

The mule with feathers sneezed.

We arrived at the Dell in the late afternoon. The air had gained a bite, and cold winds began to creep down from the mountains. We hitched the mules to a post near the lake, letting them drink to their hearts’ content.

Wikis, ever alert, tapped Day on the shoulder and motioned toward a patch of wildflowers near the tree line — not far from where we’d inspected Hothar’s hut earlier. A shape sat still among the blooms, a silhouette woven of shadow and subtle movement.

“Hey,” Day said, quietly. “Looks like he might be here.”

We approached carefully, and found ourselves standing before a tangle of limbs and stillness.

He sat cross-legged in the dirt, surrounded by wildflowers, as if the patch had grown around him. Long, lanky legs folded beneath a wiry frame, more sinew than muscle. His arms draped at his sides like vines left untethered. If he stood, he’d have easily cleared seven feet.

A pipe — not carved, but formed from a naturally hollowed curve of wood — rested between his lips. Thin ribbons of smoke drifted lazily skyward.

His face was soft and broad, almost bovine in its shape, with wide nostrils and heavy-lidded eyes. It was the kind of face built for peace. At that moment, he seemed entirely lost in it.

We all eyed each other, waiting for someone to speak.

Umberto stepped forward.

Trunch immediately threw out an arm and pushed him back, clearing his throat softly as he stepped in front.

“Excuse me… are you Hothar?”

The figure didn’t move at first. Just sat there in the wildflowers, pipe balanced between his lips, smoke curling lazily toward the clouds.

Then he spoke — a slow, low rumble, like tree roots stretching in the earth.

“Mmm.”

A long pause.

“Names’re a funny thing… don’t you think?”

He blinked slowly, eyes still fixed on some distant thought.

“Like a coat. You put it on. Wear it a while. Sometimes it fits. Sometimes it’s jus’ heavy.”

Another slow drag on the pipe.

“But aye…” He tilted his head toward Trunch. “Folk call me Hothar. So… maybe I am.”

Trunch took a careful step forward.

“We were hoping to talk to you,” he said. “About the Dan’del’ion Court. Castle Ieyoch. We’re friends of Yun.”

Hothar didn’t answer at first. Just breathed slowly through his nose, eyes still on the flower between his fingers.

“Mm. Yun,” he murmured. “Bright flame. Burns careful.”

A gust of wind stirred the wildflowers, brushing his sleeves.

“But that place… that name…” His voice softened even more, almost a whisper. “It don’t belong in mouths no more.”

He set the flower gently down on the earth beside him.

“Some things don’t grow back, friend,” he said. “Not right. Not really. You can try to mend the branch, but the scar’s still there — and it don’t bear fruit the same way.”

Then he looked at Trunch for the first time. Not unfriendly. But heavy.

“Why would you chase rot in the root, when there’s still blossom on the tree?”

There was a beat of silence.

Then Umberto exhaled, loud through his nose. His jaw clenched. His shoulders rose. His fists opened and closed at his sides like he was wringing out an invisible towel.

Steam, in the shape of a man.

“Are you kidding me?” he muttered. “We’re out here chasing whispers while they’re raising the dead and sharpening blades—”

Day put a hand on his arm. He shook it off.

“Umberto,” Din warned quietly.

But Hothar didn’t flinch. He turned slowly, pipe still balanced between his lips, and looked up at the boiling gnome.

“Mmm.”

He took a long draw, then let the smoke curl from his nose.

“Boiling water don’t see the stars,” he said.

Another pause.

“Too busy bubbling.”

Then he turned back toward the flowers, like that was explanation enough.

Trunch stepped forward again, voice steady but gentle.

“We’re not here to stir up old wounds. We just… we need to understand. What you saw. What happened in that castle.”

Hothar didn’t look up. He pinched a stalk of wild mint between his fingers and inhaled deeply.

“The wind don’t tell the tree where it’s blowin’,” he said softly. “But still, the branches bend.”

Trunch opened his mouth. Closed it. Looked to Din.

Din cleared his throat and tried a different tack.

“Hothar. You’re in danger. They’re hunting people. Everyone who went to that place. You included.”

At that, Hothar gave a slow nod. Not surprised. Not moved.

“All things are hunted,” he said. “Antelope knows the lion. Tree knows the axe. Seed knows the frost.”

He looked up at Din.

“You call it danger. I call it rhythm.”

“But if we work together,” Din tried again, “we can stop this.”

Wikis stood unblinking, head cocked to one side. Watching the firbolg intently.

“You can’t stop winter no matter how hard you try,” Hothar murmured. “You endure it. Let it pass. Plant again come spring.”

Umberto paced a few steps away, muttering curses to himself.

Trunch tried once more. “Please. Just something. A memory. A glimpse. Anything that can help.”

Hothar’s voice dropped into near reverence.

“Some soil ain’t meant to be turned.”

He tapped his temple lightly.

“Sometimes, it’s best to leave it be, don’t give the wrong things a chance to grow.”

“That’s it,” Umberto growled, stomping forward. “You’re just gonna sit here spouting gardening riddles while the rest of us are bleeding trying to fix this?”

Hothar didn’t move. Didn’t blink.

“Mmm.”

He took another pull on the pipe. “The sun can’t reach everything” he said. “Some things naturally grow in the dark.”

“Gods, I hate gardening,” Umberto muttered. He walked over to the road and began kicking at stones and pebbles, cursing.

A quiet giggle cut through the tension.

An elderly woman perched on a rock by the roadside called out, “It’s no use. All he does is talk in riddles. I reckon it’s the pipe what does it.”

Din turned toward her, exasperated. “You mean there’s no way to get a straight answer out of him?”

“’Fraid not,” she said with a shrug. “He’s always like this — unless there’s a threat to the Dell. A fire, a hunter, someone pickin’ too many flowers. If he feels the land’s in danger, then he speaks.”

Din rubbed his forehead and sighed.

“Well,” he said, loud enough for the rest of us to hear, “we are not starting a forest fire.”

The way he said it made it very clear — that wasn’t a suggestion.

Out of the corner of my eye, I saw Wikis — still watching the druid — nudge Day and motion silently toward something I couldn’t quite see. I turned to follow her gaze toward Hothar, just as Umberto pulled my attention elsewhere.

“The place needs to feel threatened for him to act, huh?” Umberto snapped. “That’s fucking great.”

He stepped toward the old woman.

“Is this threatening enough?”

His clenched fist connected with her jaw with a loud crack.

She slid from the rock, head hitting the ground with a sickening thud.

Umberto spun toward Hothar. “Is that threatening enough? Are you going to talk now?”

Spit flew from his mouth as he began striding toward the still-meditative druid.

Carrie’s wings stopped mid-beat — she dropped to the ground in stunned silence.

Trunch’s mouth fell open.

“Oh gods,” Din cried, rushing to the old woman’s side, his hands already glowing with healing light.

Yak dropped the daisy chain he’d been weaving and stepped between Umberto and Hothar.

“Ah—little help, guys? Shit. Help,” Yak called out, struggling to hold the fuming Umberto back.

“Hey, guys,” Day said calmly, beckoning. No one listened.

Hothar didn’t flinch. Didn’t even blink.

“If you leave a kettle boilin’ too long without watchin’ it,” he said slowly, “it’ll burn down your house.”

Din propped the groaning woman back up against the rock, pressing a healing potion into her hand before turning — eyes blazing — and striding through the flowers.

He hit Umberto in the face with a full gauntlet swing.

“What the fuck, Umberto!” Din roared. “A defenseless old woman?”

“Hey, guys,” Day said again, louder this time.

“I need answers,” Umberto snarled, holding his jaw. “Not fucking riddles!”

“You need to walk away,” Din growled, pointing back toward the injured woman. “And you need to be ashamed.”

“Guys!” Day called. He and Wikis were both staring at Hothar. “Watch.”

He pointed toward the ground beside the lanky firbolg.

Between the aftershock of Umberto’s outburst and the thick air of held-in fury, it took us a moment to follow his gaze. But then we saw it.

Hothar, still seated, still puffing gently on his pipe, had been running his long fingers through the wildflowers around him. Not idly — reverently. Stroking the stalks of some, gently patting the heads of others. A kind of absent-minded affection in every motion.

But when his hand neared a cluster of dandelions, it twitched. Recoiled slightly. And carefully avoided them altogether.

“Wikis noticed it,” Day said as she stepped across to Umberto “He’s been avoiding touching the the whole time.” Wikis whispered something to Umberto and they both stepped away, he seemed to sag as he so. Day continued. “I think there’s something locked away in there,” he said pointing to Hothar’s head.

Din returned to the old woman’s side, speaking softly as he helped her back onto her rock seat. His voice was low, steady — a quiet reassurance as he guided her into place and checked the bump on her head.

The rest of us remained still, watching Hothar.

He continued to weave his long fingers through the grass and wildflowers, each movement slow and thoughtful. His hand skimmed over bluebells, traced along buttercup stems — but every time it neared a dandelion, it paused, shifted, and moved around it. Not fearfully, but with quiet, deliberate avoidance.

Something about it felt… intentional.

Umberto and Wikis returned in silence, each cradling an armful of dandelions plucked from the edges of the Dell. The wildflowers swayed slightly in their arms as they approached. Even with Hothar seated cross-legged in the grass, the two stood nearly eye-level with him.

Umberto didn’t look at any of us. Not Day. Not Din. Not even Carrie, who stepped forward as if to speak but was halted by a gentle hand from Trunch. She stopped, frowning, wings twitching in confusion.

Wikis turned to Umberto. Her voice was quiet but certain.

“I think… this is how we’ll get answers.”

She gave a small nod.

Together, without another word, they lifted their dandelions and blew.

A cascade of white tufts burst into the air, drifting gently forward—soft and silent, like tiny parachutes. The seeds danced between them before settling across Hothar’s face.

He blinked.

A single twitch flickered through his cheek.

Then his eyes snapped wide. The pupils dilated instantly—huge and dark—and for a moment it looked like he’d forgotten how to breathe.

He inhaled sharply, as though the air had just returned to him after years underwater.

Then he exhaled. A long, shuddering release of breath.

“Adina,” he whispered.

His voice cracked.

“I’m sorry.”

And then he wept.