Chronicles of Klept: Chapter VI

There are few things more satisfying than a warm morning pastry and the knowledge that you have survived the night without being stabbed, cursed, or spiritually unravelled.

At least, that was the plan.

I had just returned from Baking My Way, bakers of the finest pastries in Dawnsheart, when I caught sight of the returning group riding back into town like a parade no one asked for. There was seaweed on one of them. Possibly blood on another. They looked tired but oddly cheerful.

But I had other things on my mind. Overnight, as they braved the Whispering Crypts, something else had surfaced—a revelation older, darker, and far more troubling than fish people and their manifested gods.

The Dan’del’ion Court had returned.

Not a metaphor. Not a whisper of myth. The actual court. Or what remained of it. Confirmed by multiple captured attackers, verified by the prophecy itself.

The prophecy, which—may I remind you—was never actually read aloud.

Because someone set the festival on fire.

One of the attackers was now held publicly in the stocks, which hadn’t been used in decades. Positioned in the center of the town square, a space normally reserved for open-air market stalls and ill-considered lute solos, the figure sat slumped but somehow still… watching.

The dark cloak marked them immediately as one of the attackers. The missing tongue—well, that was standard procedure, apparently.

The guards informed the group with unnerving nonchalance: “None of the captured ones can speak. All of them had their tongues removed.”

Wikis looked at the guard accusingly.

“Not by us.” He raised his hands like a man caught holding a suspiciously warm pie, technically innocent, but fully aware that Wikis was about to start flinging accusations like they were throwing knives at a circus act. It was the classic ‘I didn’t do it, but please don’t make this my problem’ pose—palms up, eyebrows high, the body language of a man who feared judgment more than guilt. “it was done before we got hold of ‘em”

“Someone doesn’t want them to talk.” Trunch was looking at the captured attacker with a determined intensity. “That’s annoying.”

While they waited for Roddrick to stumble his way into responsibility, the group attempted to interrogate the prisoner. Naturally, they got no answers—just that same vacant smile, the kind that says “I’m not stuck here with you, you’re stuck here with me.”

There was a commotion near the far side of the square—a ripple of gasps and swoons from the few early-bird market vendors and an actual squeal from one guard who was probably demoted shortly after. There she was in the flesh: bestselling author, literary sensation, and the very apex of Umberto’s deeply alarming affections. Barbara Dongswallower. Umberto, of course, missed the entire entrance.

Moments earlier, he had sidled up to the guard stationed outside Roddrick’s office with the barely restrained intensity of someone preparing to collect a debt and possibly a spleen.

“Look,” he had said, already halfway through the door, “you want him to know we’re serious, right? What better way to make that point than to be waiting in his chair when he walks in? Think of the symbolism.”

The guard, who clearly did not get paid enough to argue with gnomes in loincloths and carrying large axes, had let him in with a shrug and a silent vow to mind his own business until retirement.

So while Barbara Donswallower was illuminating the square with her radiant absurdity, Umberto was inside Roddrick’s modest office, rearranging chairs for maximum impact and muttering about invoice etiquette.

“He walks in, I say something dramatic like ‘We were beginning to worry’—BOOM, right in the guilt glands.”

He adjusted his loincloth, repositioned a quill on the mayor’s desk with the triumphant spite of someone who’s been waiting all day to prove that yes, even your desk is wrong, and settled in to wait, completely unaware that his literary idol had just arrived and was maybe eighty feet away.

The fact that she was accompanied by Lord Roddrick did not go unnoticed by everyone else, and nor did his posture, which had all the proud stiffness of a man who had finally received an invitation to the table he always imagined he belonged at.

He beamed as they strolled the plaza, one hand delicately poised behind his back, the other gesturing with unnecessary flourish as he explained a market stall to Barbara that she had absolutely no intention of visiting. To Roddrick, this was validation in silk and sequins.

High society. Real nobility. Fame.

And he was walking beside it. He had arrived.

That glow, however, flickered the moment he spotted the group of returning adventurers, or depending on your accounting practices, a cluster of increasingly expensive problems.

His smile twitched, faltered, and collapsed like a poorly pitched tent.

With a stiff nod to Barbara (who didn’t appear to notice, being in the middle of recounting a steamy metaphor involving dragons and midwifery), Roddrick reluctantly excused himself, performing a half-bow that was far too elaborate for someone backing away from their financial obligations.

Then, with all the grace of a man walking toward a very polite execution, he crossed the square toward his office – presumably to figure out how to talk his way out of bankruptcy, a divine reckoning, or both.

He was halfway across the square when he noticed his office door was already ajar.

This did not sit well with him.

His steps slowed. His smile once again twitched. He adjusted the cuffs of his coat (far too bold for the man wearing it), and cleared his throat three times before stepping inside.

The rest of the group followed—slowly, like predators giving their prey one last moment to feel safe. I trailed behind, still very much a civilian in this unfolding tale, chewing the last bite of my pastry and wondering just how awkward this next conversation would be.

It did not disappoint.

What Roddrick found inside was not paperwork, nor planning, but Umberto, comfortably seated behind his desk, legs crossed, back straight, radiating the smug authority of someone who believed strongly in the moral clarity of cash up front.

“You’re late. We were beginning to worry” the gnome announced.

Roddrick physically recoiled.

The negotiation began immediately, and badly.

By the time I passed within earshot, Roddrick was already suggesting an installment plan, something he described as “very fashionable these days—helps control personal spending, you understand.”

“You promised five hundred gold each,” someone growled.

“Which is a number with considerable weight and poetic rhythm,” Roddrick offered, as if that excused anything.

The shouting began soon after.

Fortunately for Roddrick, salvation arrived in the form of High Reader Tufulla, who burst through the narrow side door that connected his former office (now Roddrick’s gilded panic room) to the cathedral.

The door swung open with enough force to knock over a decorative sconce, and Tufulla himself looked pale, frantic, and deeply nauseated.

He stumbled forward, robes disheveled, clutched the frame, and promptly vomited his breakfast into the nearest decorative urn.

Which, for the record, was antique.

It was at that exact moment—precisely that moment—that I entered the cathedral through the main doors, rolls of sacred parchment from the archives tucked under one arm and one last satisfying bite of honeyed pastry still lingering on my tongue.

The scene inside nearly made me join Tufulla in his new morning ritual.

Two of the readers lay slain across the chapel floor, their bodies broken and surrounded by razor-thin shards of multicolored glass. There were no broken windows. Every pane remained intact, shining peacefully above the carnage like stained glass witnesses to their own crime.

The smell of something acrid hung in the air. My eyes burned. My hands trembled. I took one long look, then quietly, instinctively, backed out through the doors, as the group hurried in from the door opposite

They did not pause. They pushed past Tufulla. Din first, followed by Day, sword half-drawn. Umberto rushed through, axe at the ready. Trunch was already casting something. Wikis snapped at Roddrick, finger pointed like a loaded wand. “You stay right there!” She said it with the exact tone one uses for a dog who’s just been caught chewing on the furniture: sharp, certain, and with a look that dared him to twitch.

She clearly expected him to bolt.

While the group charged into the cathedral, blades drawn and spells humming, and I stayed precisely outside of it, trying very hard not to make eye contact with the divine carnage within—I noticed Yak.

Still in the square.

Still next to the stock-bound prisoner.

But this time, studying them.

He wasn’t interrogating, threatening, or monologuing.

He was… observing.

Shifting.

At first, just minor adjustments—a slight change to his jawline, the shade of his skin, the curve of his eyes. Practicing, I assumed. A rehearsal for infiltration. A mimicry of possibility.

But it had an effect.

Because after days of silence and stillness, the prisoner moved.

They flinched—barely—but it was the kind of flinch that comes from deep instinct, from recognition, from fear. Their lips curled into that same dark smile, but now there was something behind it.

A sound escaped them—dry, breathless, a laugh that hissed through the ruined absence of a tongue.

Air wheezing through hollow space.

Yak stopped shifting.

The prisoner’s body began to seize, just once, and then…

The mark appeared.

Just below the collarbone—a sickly, glowing sigil now pulsing red, its lines writhing like ink in boiling water.

One of the guards took a step back.

The prisoner arched forward, their mouth opened wide, and with a final airy exhale of laughter, their entire body melted into black sludge, smoking against the cobblestones.

The guards swore. One vomited. The other dropped his spear.

Yak did not flinch. But he also did not stay.

He stared at the puddle for just a moment longer, longer than anyone else dared to, then turned sharply and began walking toward Roddrick’s office with urgent, deliberate steps.

I don’t know what was going through his mind.

But for Yak to look unsettled?

That unsettled me.

Inside the cathedral, the group fanned out, searching for clues, bodies, and possibly vengeance. The air was heavy with incense and iron, the floor slick with blood. Broken shards of colored glass surrounded the fallen acolytes—but all windows were still intact.

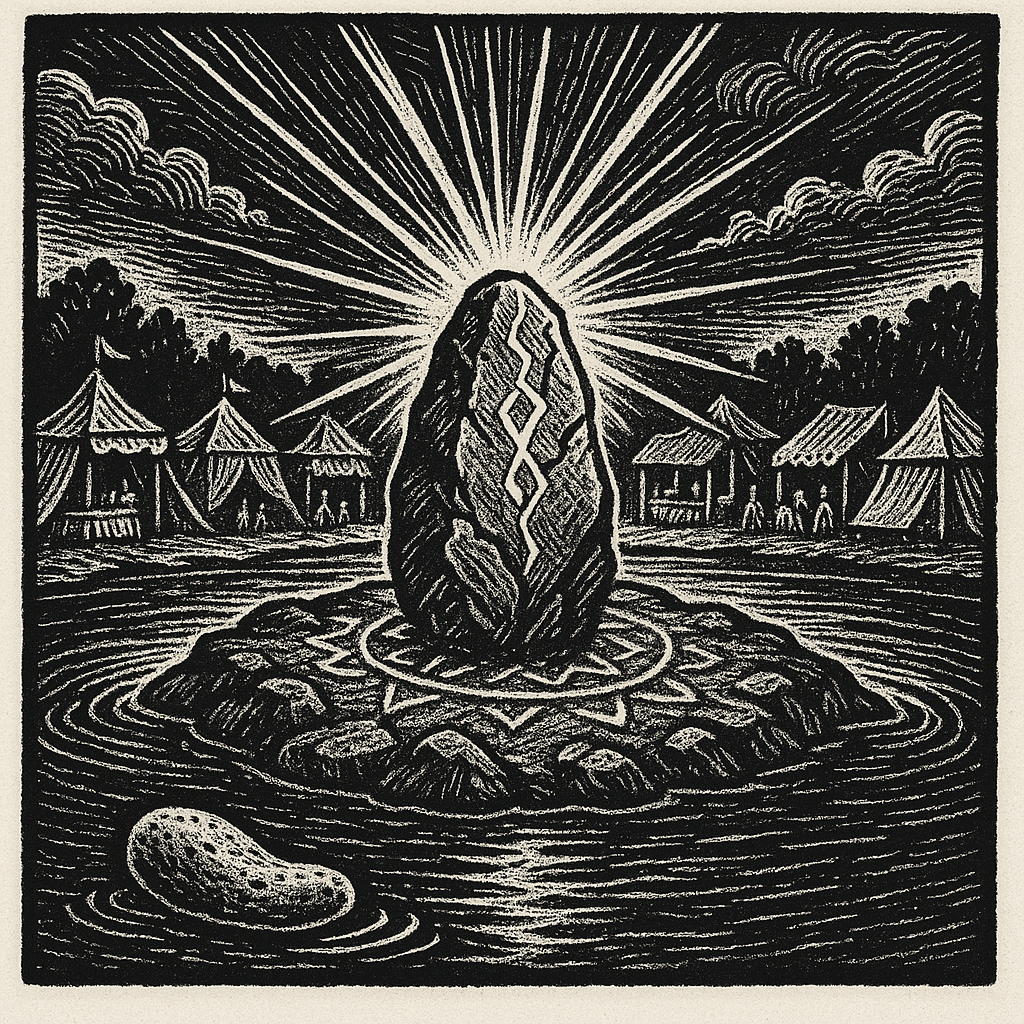

Wikis, as ever drawn to nature’s beauty even when it’s trying to murder her, had wandered to the far end of the sanctuary, gazing up at the enormous stained-glass window that formed the entire rear wall. It depicted the Prophet Rock in perfect detail—sunlight striking its surface, casting divine rays across the etched glyphs.

She stared.

And the window stared back.

No-one saw it shift.

Not in time.

It stepped out as if emerging from light itself— tall, slender, graceful, and absolutely not welcome.

The golem’s body shimmered with the colors of the cathedral’s windows, her limbs segmented like mosaic panels that moved too fluidly for glass. Her face was near-elven in its symmetry. Possibly beautiful. Absolutely deadly. She didn’t shatter the window as she exited. She stepped from it.

And the window remained intact.

Wikis barely had time to swear.

The fight was fast and terrible.

The golem moved like sunlight through crystal, flashing between windows, emerging unpredictably from the glass, each reappearance heralded by a gleam of colored light and a flurry of slashing limbs.

Day was the first to react, parrying one strike with his blade and countering with a precise incantation that set the air humming. Din’s shield sang with the impact of a blow, even as he barked orders and warding prayers. Trunch unleashed arcane energy, his hands crackling with eldritch light. Umberto noticed Barbara Donswallower.

Through the front doors of the cathedral, which I had left ajar in all the divine panic, he saw her. A blazing beacon of rhinestones and storytelling, laughing at some market stall like the world wasn’t on fire, and without hesitation, without announcement, Umberto left.

He didn’t say a word.

He didn’t look back.

He simply turned, and ran full tilt across the square toward the woman of his dreams, leaving the fight behind as if love were a tactical maneuver.

At that precise moment, Yak, having heard the scuffles and shifting his destination from the office to the cathedral, entered the fray through a window.

Now, to be clear:

The doors were open. Umberto had just left through them.

I had left them open. Wide open.

Welcoming, even.

The sensible route. The logical route.

The route any normal person, or at least any normal infiltrator attempting to not get stabbed by divine security glass, would have taken.

But no.

Yak chose the window.

The one immediately next to the open door.

And he exploded through it, stained glass shattering in a cacophony of color, and artistic regret.

He somersaulted through the air, landed in a crouch with theatrical precision, and rose slowly as if he hadn’t just committed the single most unnecessarily destructive entrance I’d ever witnessed inside a religious building.

The golem, you see, had melded with the glass.

She had stepped through, been one with the glass.

Yak stepped through as well, but only after ensuring the window no longer existed.

I decided to do something something uncharacteristically bold:

I quietly closed the front doors.

Not to trap anyone. Not even out of fear.

But because the cathedral is a holy place, and I had begun to suspect that the number of civilians gathering outside might not appreciate the sight of their gods’ sacred chamber being used as a magical slaughterhouse with impromptu acrobatics and surprise property damage.

I pulled the doors shut with great care.

Because if you’re going to bear witness to utter sacrilege, the least you can do is give it some privacy.

Wikis went down shortly after.

Struck hard by one of the golem’s vicious spinning attacks, she crumpled with a cry, arrows scattering, her hand still clutching the necklace she talks to when she thinks no one’s watching.

The group fought harder after that.

Yak moved like a ghost.

Day pressed the golem with blade and spell.

Din, still shielding Trunch, roared a prayer to the forge.

Trunch let loose a volley of blasts that cracked the air with the sound of shattering promises.

And finally—

finally—

The golem cracked. Splintered. Shuddered. And exploded into a rain of colored shards, each one landing without a sound, as if ashamed of the damage they had done.

Wikis was breathing. Barely.

The others clustered around her, pouring potions, whispering prayers, binding wounds with strips of cloth and raw desperation.

And Din, quietly, urgently, ran out through Yak’s broken window in the direction of Umberto, who was by now likely halfway through proposing a collaborative novel or challenging someone to a duel for Barbara’s honor.

“I knew he was going to do something ridiculous,” Din began, rubbing his temple with the same hand he uses to hammer steel. “He ran off the moment he saw her.”

“She glowed like moonlight dancing on silk sheets,” Umberto said from across the table, already several ales deep and staring at nothing in particular.

Din exhaled. “I ran after him. Thought he might… gods, I don’t know. Try to propose with a spell scroll. Threaten a fanboy duel. Explode. Any of the usual.”

By the time Din caught up, Umberto had already burst into the shop—The Basket of Blooms, an aggressively quaint little building with hanging baskets and a sign shaped like a watering can—and had apparently just finished professing his eternal devotion to Barbara Dongswallower, the literary hurricane herself.

The guards, her minders, had very nearly drawn weapons, having mistaken a loinclothed, sandal-wearing gnome with a massive axe and wild eyes for some kind of literary assassin.

“To be fair,” Umberto added, “it was a very passionate sprint.”

But he managed to convince them that he meant no harm.

Just… admiration. Devotion. An unhealthy level of both.

Barbara, consummate professional and mistress of theatrical charm, handled it with all the grace of a queen and the cunning of a showman. She introduced herself with a flourish, then—without missing a beat—handed him a signed parchment from a stack of them she apparently kept on her person at all times.

“They were pre-signed,” Din said flatly.

“Pre-blessed,” Umberto corrected.

Din sighed.

She started to turn away, but something – something in Umberto’s enormous eyes, perhaps, or in the desperate crack of his voice – made her pause.

She turned back. Politely wrestled the parchment back from Umberto’s grip and scribbled something on it.This time personally.

“To my new friend Umberto,” she wrote, in looping, flamboyant script,

“Sometimes the smallest Gnomes have the biggest swords.”

Then she kissed the parchment, leaving behind a perfect, bright lipstick imprint, and winked at Umberto.

Din’s voice softened just a little.

“She handed it to him. He looked at it. He clutched it to his chest like it was a holy relic and then he just… fainted.”

“I ascended,” Umberto whispered reverently. “I saw heaven, and she was wearing a feather boa.”

Din didn’t roll his eyes. He was too tired.

“I carried him back across the square like a sack of potatoes. We arrived just in time to find Roddrick was in an even bigger mess than we’d realized”