CHAPTER EIGHT

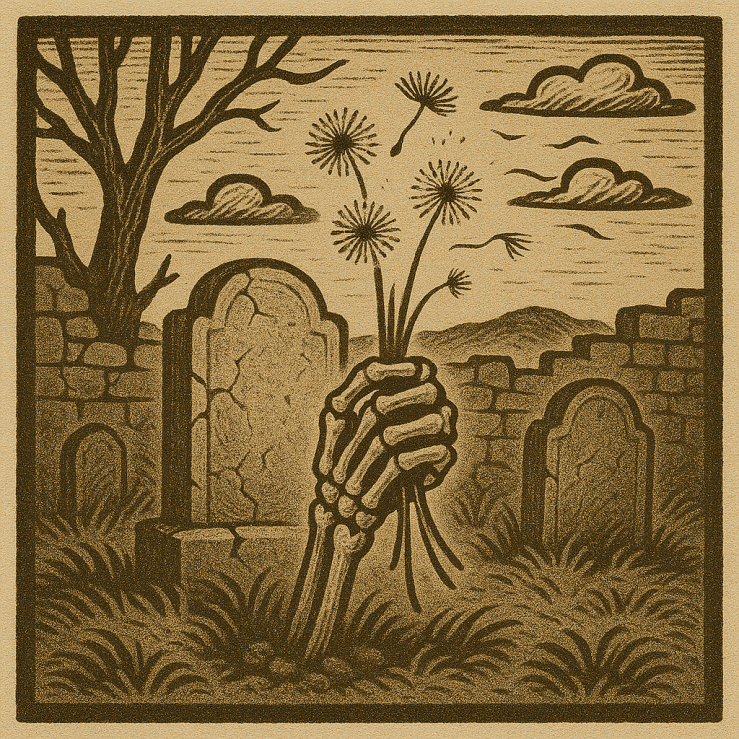

A Fistful of Dandelions

We left Dawnsheart just after noon. Battered and bruised, but they had been paid, at least. Smoke rose behind us as the cart rolled on, and Wikis muttered curses while picking glass from her hair.

The road to Nelb isn’t long. An hour by cart, less if you’re on horseback and don’t stop for existential dread. But it’s enough time for questions. And, unfortunately, answers.

“Alright,” Din said, adjusting the hammer at his back, “someone explain to me why we’re terrified of flowers again.”

“The Dan’del’ion Court,” Trunch added, from the front of the cart, “Klept, you said something about vampires. Rulers of the valley. But that’s centuries past, isn’t it?”

Day didn’t say anything. But he looked at me in that calculating way of his, the one that felt like a silent “Go on.”

I sighed, and my stomach, unhelpfully, chose that moment to growl like a caged dire weasel.

Before I could say anything, Yak wordlessly reached into his coat and produced a semi-squashed pie, as if he’d been waiting for exactly this moment.

“Stole it from the onion-and-thyme stall at the festival” he said, proudly. “Still flakey.”

He handed it over without ceremony, and I accepted it like it was a sacred offering.

“You’re a delinquent,” I said. “But a useful one.”

And as I bit into the soft, flaky pastry, something warm and nostalgic sparked at the back of my throat.

“Sulkin’s Sizzlecake,” I murmured. “Can’t wait.”

“What?” Din asked.

“It’s Nelb’s pride and joy,” I said, already drifting into lecture mode. “A pan-fried patty made of pickled cabbage, caramelized onion, root veg, and dried bread. Crisped in vegetable oil. Topped with smokey mash. Best thing to come out of that hamlet besides quiet and topsoil.”

“Sounds like a dare,” Din said.

“Sounds like home,” I replied.

“Sounds… mushy,” Carrie offered, gliding overhead.

“You don’t understand,” I said, more animated than I intended. “Sulkin’s Sizzlecake is heritage. It’s tradition. It’s breakfast, lunch, pleasure and remorse all in one bite.”

“I’ll try anything once,” Yak said with his mouth full of stolen pie.

Trunch, of course, brought us gently back to the actual problem.

“The Court, Klept. What else should we know?”

I took another bite of the pie. It was fine. Flakey, savoury, unexpectedly nostalgic.

“The Dan’del’ion Court,” I began, brushing crumbs from my lap, “ruled the Humbledoewn Valley and much of central Elandaru for centuries. Tyrants. Vampires. The kind of aristocracy that doesn’t just bleed the people dry—they drink it, bottle it, and sell it as vintage.”

I reached into my satchel and tossed something small and heavy toward Din. He caught it instinctively, blinking at the object in his palm.

A medallion. Dark metal, circular, etched with the sigil of the Court—a wilted dandelion head amongst a bed of thorns, full moon in the sky above.

“Tufulla gave it to me,” I said. “Told me to show you. Pulled it off one of the festival attackers before the guards carted him off. Possession of Dan’del’ion relics is technically illegal, so please pretend I didn’t just toss you an arrestable offense.”

“Charming,” said Trunch, turning the medallion over in his hand.

“What is it?” Din asked.

“A badge. A mark of allegiance. Back in the day, members of the Court—or their loyalists—wore these when attending ceremonies, performing rituals, or, you know, casually oppressing peasants.”

“And now they’re back,” Day said quietly.

“Or someone wants us to think they are,” I replied.

The medallion made its way around the cart, passed from hand to hand like a cursed trinket in a travelling show.

Yak flicked it like a coin, listening for something only he could hear. Umberto raised it to his mouth, clearly intending to bite it—then paused, wrinkled his nose, and seemed to reconsider the taste of ancient vampiric symbolism.

Trunch held it up to the sun, watching the silver inlay catch the light, like he was trying to read a prophecy in tarnish.

It never made its way back to me.

I suspect, though I can’t prove, that it took a detour somewhere between Wikis’ hands and her many, many coat pockets.

That quiet settled over us again—the kind that rides alongside prophecy and dread.

Up ahead, the first fields of Nelb crept into view. Rows of cabbage and onions stretched to the horizon, and beyond them, a cluster of rooftops huddled under grey skies.

The first thing you notice about Nelb is the smell.

Not a bad smell, exactly—just a very committed one. A heady blend of damp soil, root vegetables, and the kind of onion-forward honesty you only get from a town that’s truly proud of its produce.

The second thing you notice is Brandt Ulfornd.

He must have seen us coming. As we began to get closer to the hamlet he came strolling down the road. He met us just past the crooked signpost marking the edge of the hamlet—an older man with wind-chapped skin, ink-stained fingers, and the perpetual squint of someone who’d spent most of his life both reading bad handwriting and digging up worse surprises in the midday sun.

“You must be the ones Tufulla sent,” he said without preamble. “Good. We’ve got a problem.”

“That’s our specialty,” Umberto said cheerfully, already loosening his shoulders like the problem might be punchable.

Brandt didn’t laugh.

“The dead,” he said. “Some of them are trying to let themselves out.”

That got everyone’s attention.

He gestured down the dirt path toward the cemetery—a modest plot at the far end of the hamlet, ringed by low stone walls. Some sections had clearly collapsed and been patched with whatever the locals could find—wooden doors, chicken wire, two actual wagon wheels, and at least one suspiciously ornate headboard.

“We’ve barred the gates and sealed it as best we can,” Brandt continued. “But it won’t hold forever. Whatever’s stirring in there… it’s not resting easy.”

He reached into his coat, pulled out a key the size of a halfling’s arm, and handed it to me.

“You’ll be needing this. Padlock on the main gate.”

“Why me?” I asked.

“You look like the responsible one,” he said. Then, after a beat, “Or at least the one least likely to throw it at something.” Looking down, I realized I was still in my church robes. Among a group of people armed like a small militia, I was the sensible choice.

With that, he turned and began the slow walk up the hill toward his cottage, which sat perched above the cemetery like a very tired sentinel.

The wind shifted.

Somewhere beyond the gate, something rattled.

The gate hadn’t even finished squeaking when Umberto raised his axe.

One swing.

Two.

The padlock exploded into two distinct and equally surprised pieces.

“Could’ve used the key,” I offered, half-heartedly.

“Where’s the drama in that?” he grinned, already kicking open the gate like he was storming a wedding.

Inside, the cemetery was unnervingly still—until it wasn’t.

Two skeletons stood from behind opposite gravestones, all clatter and menace and the unmistakable body language of creatures that had just remembered they hate the living.

“There’s two,” Trunch noted. “But not for long,” he added, unleashing a blast of violet fire that scorched the first skeleton into aggressively motivated confetti.

“One down!” he called. “Minimal paperwork!”

Wikis dashed past him, sending an arrow flying. It went clean through a ribcage and stuck harmlessly into a grave marker behind it.

“What the fuck? I don’t miss!” Wikis shouted, watching another arrow sail cleanly through a skeleton’s ribcage and thud uselessly into a headstone. “The old man gave us useless weapons. I knew we shouldn’t have trusted him”

“We are fighting mostly bones,” Din grunted, dodging a swinging femur. “You might want to aim for something less hollow.”

“I was aiming for his chest!” Wikis snapped, stringing another arrow with the stubborn intensity of someone blaming physics for betrayal

“Maybe try using something more ‘hitty’ and less ‘pointy’,’” Din muttered, just before taking a rusty shortsword to the thigh.

“Ow—WHY do skeletons get swords?!”

“It’s historical accuracy!” I called helpfully from behind a

“It’s stupid,” he snarled, swinging his hammer hard enough to turn the offender into soup bones.

Trunch’s first blast hit true, but his second scorched the moss off a statue instead of a skeleton.

“Too far left!” someone yelled.

“No, that was a warning shot!” Trunch insisted. “It was—AH!”

A bony hand had grabbed his shoulder from behind.

Day took it out with a flick of the wrist, but not before Trunch got a jagged elbow to the ribs.

“Still alive?” Day asked, deadpan. “Don’t warn, just shoot.”

Carrie, mid-glide, waved a hand over the party, casting a wave of supportive magic.

“You’re doing amazing, sweeties! Except you! You need to duck-”

Clonk.

Yak, not used to working with aerial support, caught the butt of a skeleton’s sword across the temple while trying to flank.

“I’m fine!” he said, stumbling behind a gravestone and disappearing into the shadow.

Another skeleton shoved Wikis backwards—hard—sending her sprawling into a pile of loose headstones.

“Okay, rude!” she snapped, springing back up and stabbing it in the pelvis.

“Aim for the skull!” Umberto shouted.

“I am! It just keeps moving!”

Day was the only one untouched, blades whirling with unnerving grace—but even he was forced to retreat a half-step when three of the skeletons converged at once.

For a moment, it looked like the undead had the upper hand.

And then Umberto tackled one into a grave, shouting:

“I’VE GOT A BONE TO PICK WITH YOU”

And then Day whistled? a whisper of magic and rhythm suddenly wrapped around him like wind through silk.

In seconds, he was a blur. Steel flashed. Bones cracked. One skeleton looked down to realize its legs were no longer part of the conversation.

“Look at that. Dead and downsized.” Day murmured, not breaking stride before launching the skull toward Din. “Head’s up!”

Din spun around, a cloud of dust appeared as his massive hammer caught the skull mid-flight. “That was intentional” he called out to no-one in particular

“That’s four!” someone called.

And that’s when the fifth skeleton popped up like a badly timed sequel.

“You know,” I said, backing up behind a moderately sturdy mausoleum, “it would be great if we could not wake up the entire graveyard.”

“Yeah, but that’s not as much fun,” Yak shouted mid-somersault.

Umberto, mid-swing, grinned and shouted,

“Hey, Klept. Chronicle this!”

Then he heaved the final skeleton into a crumbling headstone near my position

It exploded in a spray of bones and pulverized granite. The largest chunk landed directly at my feet.

“Consider it chronicled,” I muttered, brushing cemetery dust from my robe and rethinking all my life choices.

The graveyard had gone quiet.

The kind of quiet that settles in after chaos, when the adrenaline begins to seep out and you’re left standing in the middle of a mess that’s only mostly finished.

Trunch was examining one of the shattered skeletons with the grim focus of someone hoping it wasn’t magical. He flicked something metallic to Day who caught it without hesitation. Din was cleaning a smear of something unpleasant off his hammer. Wikis was pacing, turning in circles like a cat that suspects the furniture is conspiring against it.

“Five skeletons,” Day muttered, wiping his hands. “Three medallions,” he held out his arm and three metallic discs hung from his fist..

“What are you suggesting?” Trunch asked, rubbing one of the discs between his fingers.

“That someone’s missing. Or hiding.”

It was Carrie who spotted it first – the mausoleum.

Larger than the others. Less weathered. Door cracked open just enough to imply it hadn’t been forced from outside.

“Ooooh,” Carrie said with a delighted gasp. “Big spooky house for dead people. And the door’s open.”

Din and Trunch approached with caution. They knelt by the threshold, examined the crumbled stonework and rusted hinges. Din’s brow furrowed.

“This door wasn’t broken down. It was broken out.”

The engraving above the doorway read simply: LENN.

Inside, the mausoleum was cool and dry. Two sarcophagi dominated the chamber—elaborate stone coffins, their lids pushed aside just enough to suggest recent movement.

Carrie flitted toward the back wall and traced a finger along the stone.

“There’s something behind here,” they said, brushing away years of dust. “A brick. Different mortar. A seam.”

Din stepped in, tools already in hand. He worked quickly—carefully— and the brick came free.

It was smooth, weighty, and marked with a familiar symbol: the wilted dandelion seed head, the thorns, the pale full moon.

Wikis took it immediately. No one was surprised.

“Don’t eat it,” Yak warned, a little late.

“I’m not eating it,” she snapped. “I’m looking at it.”

She turned it over, sniffed it, tapped it, held it up to the light like it might whisper secrets if angled just right.

It didn’t.

“Well?” Umberto asked.

“It’s… just a brick,” she said finally, squinting. “But it looks like one of those medallion things might be inside it. It’s hard to tell.”

With an exaggerated sigh, she sat down next to a slightly raised patch of earth and set the brick beside her.

There was a pause.

The ground shifted.

Then a skeletal hand broke through the soil where Wikis had just placed the brick on top of a grave.

She froze.

Then, with grim efficiency and a slightly wild look in her eye, she stabbed it. Not once. Not twice. Repeatedly. As if the skeleton had insulted her boots, her haircut, and her entire bloodline in one sentence.

“Oh no you don’t,” she hissed. “You stay dead!”

The torso wriggled up, ribs gleaming in the afternoon light.

Umberto sighed—long and theatrical.

“I am so done with this.”

He stepped forward and, without ceremony, stomped the skeleton’s skull into the ground with the flat of his boot.

There was a satisfying crunch.

“There,” he said.

Wikis didn’t stop stabbing for another two seconds.

I, from a safe distance, made a note:

“Post-mortem vengeance, if executed decisively, can be quite therapeutic. Possibly contagious.”

Trunch stepped forward, eyeing the brick still resting beside the grave like it might sprout legs.

“Don’t leave that lying around,” he said evenly. “Put it in a bag. Deep in a bag. Preferably under something heavy. And preferably not next to anything we might value, trust, or be fond of.”

Wikis scooped it up reluctantly and shoved it into her coat, muttering something about everyone being dramatic.

“We should probably have Tufulla take a look at it,” Din said, matter-of-factly.

Umberto grunted. “Or we smash it now and save ourselves the trouble.”

Wikis said nothing—just slipped it into an inner pocket and patted it once, like it might bite.

Like three old stones weathered by different storms, Trunch, Day, and Din gathered near the mausoleum—one stern, one silent, one searching. Together, they watched the ground as if it might still hold answers.

“Five skeletons,” Trunch said, rubbing a smear of bone dust between his fingers. “Three medallions. That bothered me at first.”

“And now?” Day asked, arms folded.

“Now I think the brick explains the rest.” He gestured vaguely toward Wikis’ coat, as if the cursed object might start rattling at any moment. “It was placed directly between the sarcophagi. It could be another trigger.”

Day considered that for a moment, then tilted his head slightly.

“You think the medallions raise the dead?”

“Maybe,” Trunch said. “Three of the skeletons had medallions. Two didn’t. There are two empty sarcophagi, which would account for the extra skeletons.”

Din knelt beside a patch of disturbed earth, glancing back toward the mausoleum.

“The brick was placed precisely,” he said. “Dead center. The sarcophagi weren’t even sealed properly. Whoever put it there either expected the dead to rise… or wanted them to.”

“So, the mystery skeletons are Mr. and Mrs. Lenn then?” Carrie called out, not looking up from where she was cheerfully doing rubbings of a headstone. “Rude of them not to wear name tags.”

Day, ignoring her, nodded slowly.

“Normally,” he said, “another skeleton rising in the middle of a graveyard fight wouldn’t be strange.”

“Skeletons rising is strange by nature,” Carrie called from somewhere among the headstones.

Day didn’t look at them, just kept watching where Wikis had set the brick.

“Stranger then,” he clarified. “Because it didn’t just happen. It happened right after she put the brick down. That’s not a coincidence. That’s a connection.”

The group gathered together at the graveyard entrance.

“This seems too specific to be random,” Trunch said

“We could go back,” Wikis offered, scanning the graves again. “Tell Tufulla what we saw – give him his stupid bow back” holding the bow out at arms length and giving it a look as if it had just embarrassed her in front of royalty.

“We could,” Carrie said, drifting gently above the cracked headstones, “but wouldn’t that be boring?”

I was quietly leaning toward ‘sizzlecake,’ but no one asked me.

“We should find out more about the LENN family,” Trunch said. “If there’s a bloodline still here, it might explain the activity. Someone’s stirring the old blood.”

“Agreed” Din was looking at the mausoleum “That brick had to be there for a reason.”

“Brandt!” Carrie declared, beaming with the pride of someone who thinks they’ve just discovered butter goes on hot corn cobs. “He’d probably know.”

I did not sigh. Not audibly. But internally? There was a whole opera.

Yes, by all means, let’s consult the man whose graveyard looks like it was curated by neglect and possibly raccoons. Don’t ask the chronicler who spent two winters mapping the valley’s family lines by candlelight and spite. No no. Ask the man whose house looks like it’s been losing an argument with the wind since the last harvest.

Brandt’s house sat crookedly on the hill, leaning slightly to the left like it was thinking of giving up. Shingles missing, porch half-collapsed, chimney held together by prayer and moss. It matched the graveyard perfectly—headstones toppled, names obscured, weeds tall enough to qualify as wildlife. Nothing in this place looked cared for. Not recently. Not passionately.

The others started up the worn path.

Then Din stopped.

He squinted into a far corner of the cemetery—dense brush and ivy-choked stone, wild even by Nelb’s relaxed standards.

“What is it?” Umberto called, his tone part concern, part boredom.

Din didn’t answer immediately. Then, without turning:

“I’ll catch up in a moment.”

Umberto cupped his hands around his mouth.

“If something else decides it doesn’t want to be dead anymore—try a battle cry this time, not one of those startled little screams.”

Din raised a single finger in reply, not stopping, not turning, he just kept walking into the overgrowth, eyes fixed on something none of us could see.

The rest of us paused, then moved on. No shouting. No urgency.

Just that lingering feeling that something hadn’t quite finished.